This Fan Post Was Promoted to the Front Page by Anton Tabuena

[Note: many of the passages from contemporary sources contain derogatory and offensive terms in reference to various ethnic groups. While I in no way condone the viewpoints expressed with their use, I also do not condone pretending such sentiments did not exist. For that reason they have been left in and hopefully do not detract from your reading experience.]

This is part four in a four part series shining a gas light on the forgotten golden age of mixed martial arts that existed during the Belle Époque. For the previous installments in the series, check out Part 1: The Golden Age of Wrestling and the Lost Art of American Catch-as-Catch-can, Part 2: The Rise of Judo and the Dawn of a New Age, and Part 3: Sherlock Holmes, Les Apaches, and the Gentlemanly Art of Self Defence. And for the history of the origins and early development of MMA, read James Figg: The Lost Origins of the Sport of Mixed Martial Arts.

The way the Ultimate Fighting Championship was created was a bunch of television guys got together and said, "Let's answer the age-old question, which fighting style is the best?" Would a boxer beat a wrestler? Would a kung fu guy beat a karate guy?

- Dana White

The fact is that when started this, it didn’t exist. We started it… they didn’t know what it was…

- Bob Meyrowitz, TOTAL MMA by Jonathan Snowden

Autumn of 1993 proved to be pivotal season in the history of combative sports. In September of that year Masakatsu Funaki’s Pancrase held their inaugural event, one where, for the first time in memory, professional wrestling matches were contested for real. It was only fitting that a promotion named after the ancient Greek sport of pankration, a sport that combined boxing and wrestling in an "anything goes" contest, would now be hosting matches where slams, kicks, punches, knees, elbows (but no strikes to the head except for those with an open hand), and all the "sleeper holds", leg locks, and other submission hooks of "worked" pro wrestling would finally be used for real.

A few weeks later, on November 12, an even more significant event took place: the initial Ultimate Fighting Championship. Advertised as a "no holds barred" contest between a "sumo wrestler, savate champion, kick boxer, karate specialist, jujitsu whiz, cruiserweight prizefighter, "shootfighter" and tae kwon do expert" to find the ‘Ultimate Fighter". "People were intrigued by the concept of style versus style." Dave Meltzer explained in Total MMA, "People have debated that forever. What if a wrestler fought a boxer or a jiu-jitsu guy?" The event would prove a success, capturing the public’s imagination and giving birth to what would be known as mixed martial arts, a sport the likes of which the world hadn’t seen since pankration went extinct 1500 years ago.

Of course, anything go matches had not died out with the Greeks and Romans, and mixed fights between boxers, wrestlers, savateurs, judokas and other disciplines had already taken place, having answered all our questions during the era known as the Belle Époque.

The "age-old question" of who would win between a boxer and a wrestler is one that was actually rarely asked until the 20th century. Before that, in the time of London Prize Fighting, the two disciplines were so intertwined that such a debate would be viewed as pointless: a great number of boxers were wrestlers and a great number of wrestlers were boxers. Being skilled in wrestling was in fact viewed as essential to any boxer, with many victories gained due more to grappling and throwing your opponent to the ground than to the power or precision of one’s strikes. For evidence, one needs only look at the 1825 training manual "The Art and Practice of Boxing" by A Celebrated Pugilist (Anonymous) where they will find that of the eight illustrations contained within, nearly half are dedicated to such "boxing" techniques as the "cross bullocks", "throwing", and "locks".

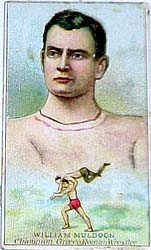

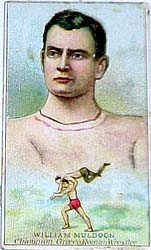

Mixed competitions between wrestlers and boxers (or, more precisely, wrestlers who boxed and boxers who wrestled) did take place, but were viewed very differently than later discipline versus discipline match ups. They instead often resembled the mixed wrestling matches of the time, were wrestlers would compete in two or more styles (catch-as-catch can, collar-and-elbow, Greco-Roman, Cornish, Cumberland, Westmorland and even sumo), alternating between them after every "fall" in a best of three or best of five contest. One such mixed boxing and wrestling match was arranged between William Muldoon and the Australian Professor William Miller in the city of Baltimore on the 25th of June, 1888. Unfortunately, only the first match of boxing was completed (with Professor Miller gaining the decision in 12-rounds over the "Solid Man" Muldoon with both men wearing 4 ounce gloves) before the police stopped the illegal prizefight.

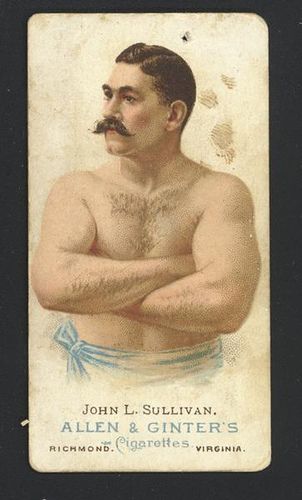

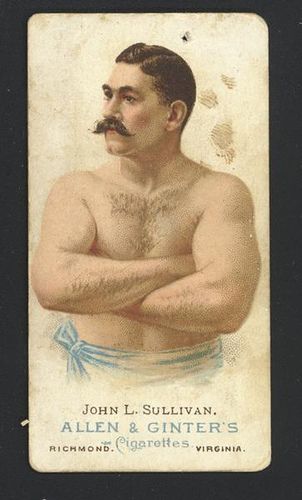

A year later in Gloucester, Maine, Muldoon faced off against his pupil, the "champion of all champions", bare-knuckle boxer John Sullivan, in the best remembered boxer versus wrester contest of this period. Muldoon had been training the "Boston Strong Boy" for his upcoming bout with Jake Kilrain, and his methods, while affective, were so harsh and sadistic that by this time John had come to despise Muldoon. The match itself was 2-out-of-3 falls and Sullivan made a good showing, gaining the first fall, but eventually, as the New York Sun reported, "Wrestling Gladiator William Muldoon tossed Pugilist Gladiator John L. Sullivan." After winning the second round, Muldoon would go on to take the third and deciding fall when "he just picked Sully up and slammed him to the carpet…the fall seemed heavy enough to shake the earth." Following his defeat Sullivan raised his fist and threatened his tormentor Muldoon with a sledgehammer blow but by this time the crowd of 2,000 spectators had rushed the ring, preventing any post-match altercations.

Another famed wrestler of the period who engaged boxers was the catch-as-catch master, Joe Acton, who not only faced the previously mentioned Professor William Miller in Philadelphia in 1888 but the future World Heavyweight champion Robert "the Freckled Wonder" Fitszimmons in San Francisco in 1891 as well. The Angeles Times reported the latter outcome as: "The Pugilist Secures One Fall, but the "Little Demon" Proves Too Much for Him in the Two Other Bouts". Afterwards, Bob Fitzsimmons would himself go on to meet William Muldoon’s chosen heir to the Greco-Roman Championship, Ernest Roeber, in a series of matches that included wrestling, boxing, an alternating mixed competition, and even reportedly a true boxer versus wrestling match in which "Fitz took a punch or two. Then Roeber grabbed him, tied him into knots, and the show was over."

Apparently tired of facing superior grapplers, Fitzsimmons would meet fellow boxer Gus Ruhlin in a wrestling match in 1901 at Madison Square Garden. The two had met the year before in a gloved boxing match where Fitzsimmons proved victorious, beating Ruhlin unconscious in the 6th round, but in the interim year prize fighting had again been banned in New York forcing the two to take up the mat game full-time. The contest between them demonstrated how loose the definition for "a wrestling match" could be, especially when pugilists were involved, as the two of them freely adopted boxing tactics, "and with the exception that they didn’t close their fists, the encounter resembled in every way a boxing match." Ruhlin would go on to avenge his earlier defeat, winning in straight falls.

With the ascension of the Marques of Queensbury Rules, boxing metamorphosed from the heavy grappling London Prize fighting to a purely striking sport. This divergence created a stark contrast between the two disciplines, causing some to now ask "which of the two would have a better chance in a fight between a wrestler and a boxer?"

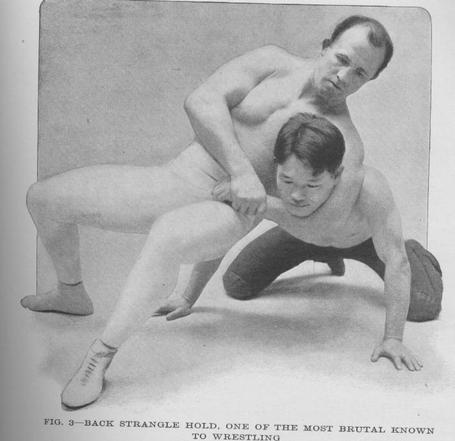

In hopes of answering this question – and sell tickets - promoters soon were pitting wrestlers against boxers in either of two different sorts of matches. The first, were "all-in" professional wrestling matches were boxing tactics would be permitted as long as no close-fists were thrown. Former boxer "Denver" Ed Martin took part in such a match against the "The Russian Giant" Jack Leon, where his strategy consisted of "slapping the Russian in the face with the open hand when he tried to rush in." The second sort were true boxer versus wrestler matches, with the boxer adhering to the Marquis of Queensbury rules while the wrestler conducted himself according to the rules for of his sport.

Matches of this sort were not limited to the United States. While mixed prizefights were forbidden by law in England (although exhibition matches were allowed), they were not banned in the rest of the Empire and proved particularly popular in the Commonwealth of Australia. An example of such a match took place in Melbourne in 1911, when a boxer, a Mr. W. Meeske, and a wrestler, a Mr. Warrington, were pitted against each other "so that those present might form some idea of which was the better method of self-defence. The boxer, who was only allowed to hit, and not to hold, got all the worst of the bout. Once only did he make much impression on the wrestler, who succeeded in getting hold and throwing him heavily several times."

Many of these sorts of mixed matches were held in Australia and at one point a Clarence Weber, identified in the papers as a "champion wrestler, weight-lifter, and physical culturist", even challenged the heavyweight boxing champion of the world, Jack Johnson, to an "all-in" fight. Johnson, who had also engaged in professional wrestling matches in Europe, apparently accepted the challenge but for whatever reason (perhaps Mr. Weber came to his senses) it never materialized.

Even with the aborted Weber-Johnson duel, the answer to that "age-old question" was soon clear, as the 1918 Middle Weight Inter-Allied Games champion Paul Prehn explained:

There has been a great deal of discussion of late as to the outcome of a mixed bout between a wrestler and a boxer. The author has conducted many bouts of this kind in and out of the army, seen and heard of a great many others, and only once remembers of a boxer winning.

While the great "boxing versus wrestling debate" ended rather quickly in wrestling’s favor, another, even more passionate debate soon came to the fore between the supporters of boxing and the foreign upstart jujutsu. It started soon after Edward-Barton Wright had imported several Japanese "champions", including Yukio Tani and Sadakazu "Raku" Uyenishi, to London to assist in advertising his "New Art of Self Defense". The two, along with the exotic jujutsu they introduced to Europe, proved to be a sensation amongst the public and their music hall appearances sparked a lively debate. In 1906 a series of articles and letters were published in "Health and Strength" Magazine (and was possibly orchestrated to publicize the magazine’s release that year of a pair of instructional manuals dealing with the two "antagonistics"), asking as to whether a boxer using the "manly British art" could beat a jujutsuka and his "arsenal of useful tricks" in a regulated contest. A letter from W.H. Hall to the editors at "Health and Strength" provides a sample of the boxing supporters thinking in regards to jujutsu:

Hitherto there has been some doubt expressed as to the result of a boxing v jujitsu contest. It seems that quite a number of people labour under the erroneous idea that jujitsu is more effective than boxing as a means of self defence. This notion however, is quite unfounded, as there has never been an instance on record where jujitsu has gained a victory.

It wouldn’t take long for Mr. Hall’s statement to be proven false, for that very year Yukio Tani traveled to Paris to engage in such a boxer versus jujutsu bout at the Circus Bostoock with Marc Gaucher, "one of the best known Parisian masters of English Boxing." The rules for their match had been written up by Gaucher himself, and were to be as follows:

1. The match has to be fought in ten rounds of two minutes, with breaks of one minute in between.

2. If Yukio Tani fails in making me give up in this ten rounds, I should be the winner.

3. Twisting of fingers and catching the others eyes or genitals is forbidden; blows are only allowed to be landed above the girdle and only the normal grips of Jiu-Jitsu are permitted.

4. For me gloves with a weight of eight oz. are determined.

- BOXEN UND JIU-JITSU, from the February 11th, 1906 Vienna Allgemeine Sportzeitung

Yuko Tani would see to it that the match wouldn’t see the 3rd round, let alone the 10th. In the 2nd round, after Gaucher struck him with a right to the side of the head, he seized his opponent and brought him to the ground where he quickly applied a stranglehold to end the bout.

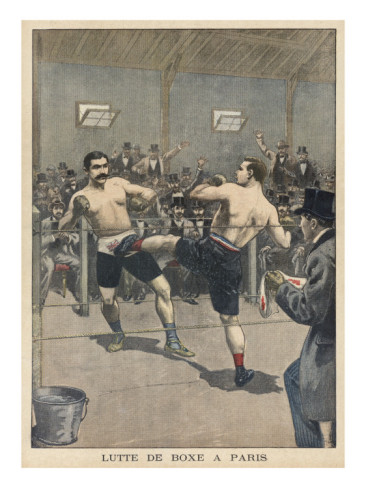

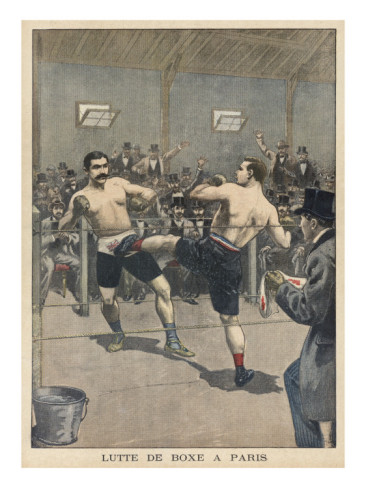

Such mixed competitions were nothing new to the people of Paris, with contests between wrestling (both la lutte parisienne and la lutte libre), la boxe anglaise, and savate taking place as far back as the 1850s. A revival of these bouts begins at the fin de siècle starting with boxing versus boxing matches – English boxing against boxe française. The most celebrated of these matches took place in Paris on October 28th, 1899, when Charles Charlemont, the son and successor of Joseph Pierre Charlemont and one the greatest savatuers of the era (the other being Victor Casteres who had defeated an English boxer the previous year in a match that was personally judged by the Marquis of Queensbury), faced the ex-champion of the Royal Navy and representative of the opposing English style, Jerry Driscoll.

http://cdn2.sbnation.com/imported_assets/853714/charlemont-v-driscoll.jpg

The match itself left much to be desired. Almost immediately Driscoll claimed Charlemont had bitten him. There were reports from English witnesses that the timekeeper had saved the Frenchman several times. There were numerous stops and starts by the referee, who at one point refused to continue the match, but was persuaded to proceed. And finally there was the conclusion, with Driscoll falling to the ground clutching either his abdomen or groin after receiving a kick from Charlemont in the eighth round. The Englishmen in attendance claimed the winning strike was to the groin and thus a "foul". French spectators reported the victory was due to a fouetté median – a round kick to the stomach. While the French press seemed to claim the match a victory for la savate and the French style, the English press roundly ignored the results so that other such la savate v boxing contests would be required to decide the matter, although these proved equally inconclusive.

While the argument over boxing or savate was left undecided, the French public (or at least the periodical "Lectures pour Tous") had already moved on, turning its attention to the matter of "Jiu-Jitsu ou Boxe Française?" To settle the debate a contest was arranged in 1905 between la savate and fencing master George Dubois and the jujutsuka Ernest Regnier, with the articles of agreement, according to the Decatur Daily Herald, being "everything goes but the biting and gouging. The Fenchman will kick and punch at his pleasure and the Jap is permitted to use all the bone-breaking holds at his repertoire. The crowning bit of humor is the proviso that the ‘referee will stop the contest if it becomes brutal’."

The paper mistakenly identifies Ernest Regnier as Japanese, a common mistake as he went by the nom de guerre Re-Nié. In truth Regnier was a French Greco-Roman wrestler who after being introduced to jujutsu by the Parisian physical culturist and former student of the Bartitsu Club, Edmond Desbonnet, took up the art at the Oxford Street Dojo under the mentorship of Taro Miyake and Yukio Tani.

The contest was held October 26 of 1905, in a ring set up outdoors "in an icy wind" on the terrace of a factory. It was a private affair which drew a distinguished crowd by invitation only. The "whole of sporting Paris was present. The celebrities of boxing, the kings of motoring, and famous fencers were pressed around the arena, and almost ever member of the sports press was there to record the event." Most of those present wore top hats, while the two combatants were only slightly less formally dressed in evening jackets.

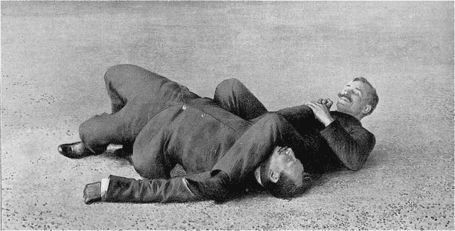

The match, as described by L. Sauveroche in the November 4th, 1905 Edition of the L’Illustration, was a brief affair:

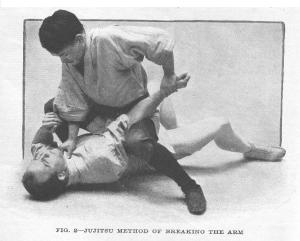

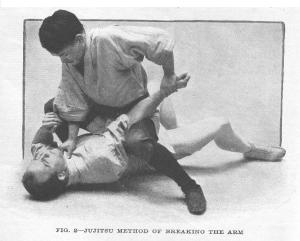

Dubois tries a right low kick that Re-Nie dodges. Dubois then tries a side kick with the same leg, but at the same time, with extraordinary timing Re-Nie leaps like a cat over the kick and grabs Dubois around the waist. Dubois tries a hip toss: Re-Nie blocks and moves to the right of his opponent, puts his right hand on the abdomen of the Dubouise and at the same time pushes his left hand into the the lower back and sends a knee in the right thigh. Dubois topples and falls on the shoulder blades in a heap, Re-Nei follows him down and siezes his right wrist. Re-Nie then turns Dubois to the left onto his back, passes the left leg across the throat. This done, he pulls violenty against the arm-joint of his opponent; the hold which can dislocate the elbow, provokes such pain that Duboise, after attempting to stand for a second, then begs for mercy.

The fight had lasted just 26 seconds, 6 seconds for the engagement itself.

After the match newspapers as far away as the Atlanta Constitution in the United States of America and the Fielding Star in New Zealand reported the results. Regnier’s patron Desbonnet wrote that upon his victory "Immediately, all of Parisian aristocracy had enrolled for classes" in jujutsu. Perhaps the most far-reaching consequence was that Dubois himself became a student of Regnier’s afterwards incorporating jujutsu with his knowledge of savate, fencing, and wrestling to assist in the development of defense dans la rue and eventually penning the self defense manual "Comment se Défendre".

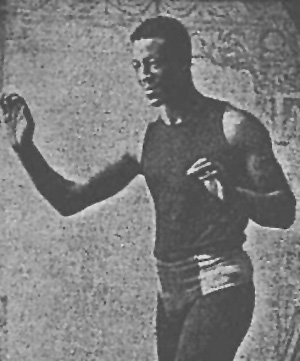

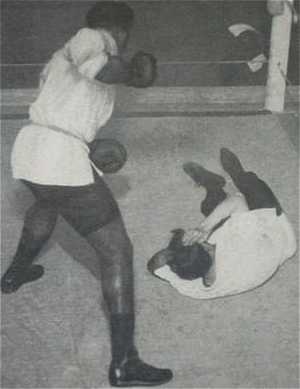

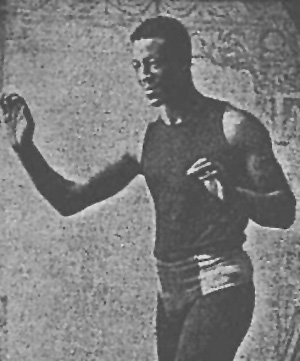

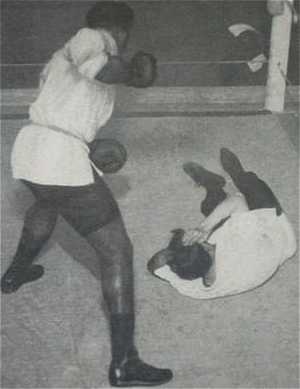

Another, similar bout with very different results, took place in Paris on December 31st, 1908, when the great American boxer Sam McVey met the judoka Tano Matsuda. The future "colored heavyweight champion" McVey was gaining a mystique as "L’Idol of Paris", so there was a great deal of interest and pageantry surrounding the event between him and his opponent who was advertised as a "Japanese master of jiu-jutsu". In truth Matsuda was not Japanese, but an Englishman named Payton who had limited skills – if any – in jujutsu and would provide no competition for McVey. "McVey charged across the ring at the start of the bout, feinted Matsuda with his left, and ripped a right uppercut to the chin that flattened the jiu-jitsu master." The duration of the fight was all of eight seconds.

The interest in these mixed competitions soon spread across the Rhine, where only a few days after Tani’s victory over Gaucher, another jujutsu versus boxing match was staged at the Zirkus Schumann in Berlin. Representing jujutsu would be Katsuguma Higashi, who had arrived after stints in New York and London, while that old hand of mixed competitions, Robert Fitzsimmons, would be serving as boxing’s champion. The results proved disappointing to those in attendence.

Circus Schumann had a big day yesterday. Higashi, the representative of the Japanese fighting sport, Jiu - Jitsu, had finally set himself against R. Fitzsimmons, the American boxer. The house was full to overflowing, but the crowd did not quite get its money's worth, because the fight between the Japanese and the American was short. After four minutes Fitzsimmons had to excuse himself because of exhaustion and so was declared defeated.

- "The Victory of the Jiu Jitsu", Berliner Tageblatt, February 9th, 1906

The finish would either be blamed on the fact that Fitzsimmons had been suffering from a rather violent cold and thus was unable to put on his best performance or credited to Higashi using a strangulation technique that the audience was unable to appreciate. Either way, the public displeasure over the surprising shortness of the fight did not prevent future matches of a similar vein from taking place. The very next year another mixed competition was held in Berlin, this time between the boxer Paul Maschke (alias "Joe Edwards") and the self-styled jujutsuka Edmond Vary. Maschke would gain a victory for boxing, setting up a rematch later that year. Eric Rahn, a noted jujutsu and judo pioneer within Germany, seconded Vary for this fight, and later recounted the experience:

The meeting took place in the Circus Busch. I was asked by Vary at the last minute to function as his second and explained that although I had no idea about his ability, I was willing to serve. The fight was disastrous for the so-called "Jiu Jitsu master". Consequently, both force- and talent-less he stepped forward and was then felled by a straight punch to the nose. He attempted to trip his opponent while on the ground, but the boxer simply evaded these attempts. I realized that he had no prospects for victory and proclaimed that he had been defeated.

- "50 years Jiu Jitsu and judo; The invisible weapon with Erich Rahn" by Eric Rahn, 1950

Such mixed matches continued, albiet illegally, in Germany and Vienna for some years afterwards. Erich Rahn would himself be challenged by and engage with several boxers immediately following the Great War.

Jujutsu or judo versus boxing contests were not limited to Europe. They proved remarkably popular amongst the nations of the Pacific where they were known as "Merikan", a Japanese slang for American fighting. "Merikan" contests may have actually taken place as early as the 1890s, but the oldest account given is from the 1909 Manila Carnival in the Philippines:

The bout was to be two falls or knockdowns out of three. The Jap was to wear a sort of jiu-jitsu shirt while the American was to wear gloves. The Jap was not allowed to hit but all jiu-jitsu holds were permitted. The American was not allowed to wrestle or hold but all clean blows were permitted.

The gong rang. Quicker’n you can say ‘Sap,’ the Jap grabbed ye scribe by the right arm, twisted and pitched us on our ear in a neutral corner some fifteen feet away. One fall for the Jap. After we got the resin well out of our ear we arose only to find the little brown brother right on top of us again. But this time we beat him to it with a sweet right hand, inside and up. The little rascal only weighed 98 pounds while we displaced some 124 at that time. So we take no credit for the fact that the gent from [Tokyo] folded his tent like an Arab and silently stole out of the ring. He forfeited the third trip to the canvas, explaining that he did not expect to get hit, being under the impression that the gloves were only used as a handicap for the difference in weight.

- Harvey "Heinie" Miller, "Now You Tell One!" Ring, Dec. 1922

"Merikan" fights would not only continue to be held in the Philippines but would spread throughout the Pacific Rim. In Australia, the boxing versus jujutsu debate sprung up anew, and both sides were soon issuing challenges to each other (with some using the vilest of racist reasoning to support their claims). The most interesting of the resulting matches may have been the one between Ryugoro "Shima" Fukushima and "Jack" Howard in Melbourne in 1912. According to publications, "The conditions were that Howard was to be allowed to hit at all times and under all circumstances, while Shima was to follow the rules of jiu-jitsu. Howard was to wear 8oz glozes, Shima was not to hit with clenched hands, and there was to be no kicking." The match was a wild and wooly affair, with the boxer Howard knocking out Fukushima in the first of a best of three contest, only to have his Japanese opponent grab his legs in a "scissors grip" and force him to surrender in each of the next two contests.

Sam McVey also made an appearance in Australia to try his hand in another mixed bout, against the questionable "jiu-jitsu champion" Professor Stevenson who had probably done more to usher in the "all-in" mixed fighting craze in Australia than any other individual. The match would prove much more competitive than McVea’s last, with the boxer tapping out for two of the rounds before prevailing with a knockout of Stevenson.

In Hawaii the first recorded match took place in Honolulu on Dec 30, 1916, when professional wrestler and judoka Taro Miyake defeated boxer Ben de Mello. For years afterwards jujutsu versus boxing contests (along with other mixed disciplines fight) would be held on the Islands, the most notable of which took place over the Spring of 1922 and involved the English Boxer Carl "Kayo" Morris against Professors S. "Speed" Takahashi and Professor Henry Seishiro Okazaki. Morris would split a pair of matches with Takahashi, knocking out the jujutsuka in their first match in only one minute and twenty-eight seconds, and then go on to lose the rematch in the third round when Takahashi "threw Morris forcefully onto the canvas and applied a head hold". A short time after that Kayo would go meet Professor Okazaki in a ring with the rules being:

Morris would wear a sleeveless jacket and six-ounce boxing gloves. There would be six, three-minute rounds. If Okazaki fell to the mat, Morris would have to go to a neutral corner. If Morris fell, Okazaki could work on him on the ground. Okazaki was prohibited from applying strangle holds using both hands, chopping (shuto) to the face, kicking with the toe (tsumasaki geri), gouging the eyes with the fingers, and punching with the fists

- Jiu-Jitsu vs Wrestling and Boxing: Three Months of Electrifying Mixed Matches in Hawaii by Charles Goodin (2005)

During their bout, Morris would break Okazaki’s nose in the opening round before, in the second:

Okazaki threw his opponent to the mat and with an arm lock which wrenched the muscles of Morris' right arm and forced him throw up the sponge.

At first sight, it looked as if Morris' arm was broken, but after an examination by Dr. S. R. Brown, who was present in the audience, it was found that the muscles were merely badly wrenched.

-"Morris Has No Chance Against Jujtsu Expert",Hilo Daily TribuneMay 19, 1922

Merikan matches were also reported amongst the Western and Japanese expatriates of Hong King. In the spring of 1923, at the Theatre Royal, the Australian boxer Nick Boyle was pitted against the jujutsu practitioner Tomikawa in a contest that was to be for either six two-minute rounds or to the finish (Boyle would end up losing to Tomikawa in the second round). Tomikawa would go on to face James Peets of Manila with the Japan Times reporting that "Peets, although a big fellow, was easy for the Jujitsu man."

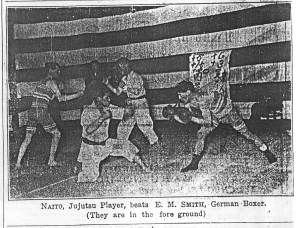

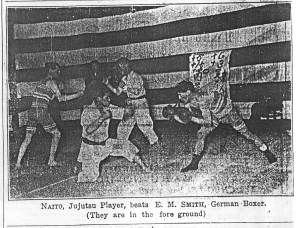

In no place did these "Merikan" fights prove more popular nor were they staged as numerously as in jujutsu’s home country of Japan. A 1913 article by the Japan times reported on an exhibition that was holding up to a dozen matches a night and drawing full houses every evening at the Yarakuza. Amongst the more interesting results given for the matches was one where "Seven times boxing champion Cally faced his jujitsu contestant Kawashima with vigor and enthusiasm only to be mercilessly defeated by the Japanese 'boy.'" Another match described how "the close fighting between Naito and Smith was another attraction. In this also Smith, the German boxer unfortunately showed that he was far from being a match to the Japanese banner-bearer."

Large events hosting several Merikan matches continued well into the next decade with the Japan Times reporting that on the 10th and 11th of May, 1924, that there was to be in Tokyo "a contest of 'Judo' and boxing between Japanese experts and Americans" with up to a dozen of each participating. A year later Yokohama city officials organized a display of boxing versus jujutsu matches to welcome Vice-Admiral Sir Alexander Sinclair and his British Asiatic Fleet flagship HMS Hawkins.

The rivalry between boxing and jujutsu, as well as the one between boxing and wrestling, was soon eclipsed by the feud that arose between the two disparate grappling arts of jujutsu and wrestling. In the first few years after Edward Barton-Wright had arrived in London with his Japanese ‘champions’, jujutsu had found nothing but success. From the music hall stages demonstrations against the native wrestling folkstyles were held and inevitably audiences found themselves amazed at the apparent ease with which these diminutive foreigners could defeat their giant wrestling heroes.

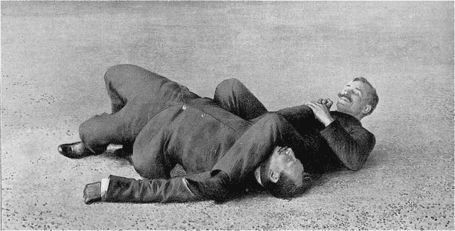

A prime example, as described by Armand Cherpillod in his 1933 autobiography La Vie d’un champion (co-authored by Abel Vaucher), was the encounter between Sadakazu "Raku" Uyenishi and a Russian wrestler and strongman named Klemsky, who claimed his neck was too strong for him to be choked unconscious.

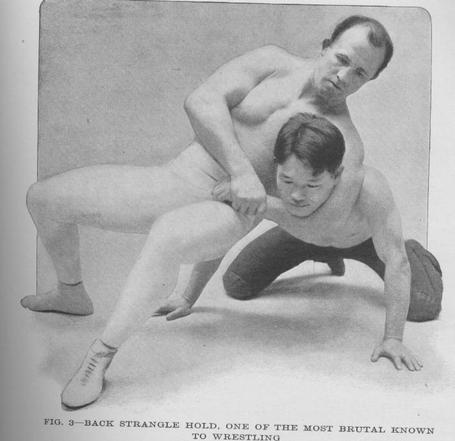

As quick as a flash, the Japanese leaped onto the Russian and seized him by the collar of the jacket, one hand on each side of his neck, by crossing the wrists, and learnedly exerted the famous pressure on the carotid arteries which brings choking, and even unconsciousness. The hold did not seem to have any effect on the Russian who simply smiled at the audience. Astonished by this resistance, the Japanese wrestler’s eyes gleamed with malice. He rolled across the ground past the Russian while preserving his hold and, to increase the force of the pressure on the neck, planted his two feet in the pit of Klemsky’s stomach. This tightened the grip so extremely that a net of blood escaped from the mouth of Klemsky and sprinkled his face. It was only then that Yanichi [Uyenishi] released his hold and let fall beside him the apparently lifeless body of the Russian.

The public believed that Klemsky had died. They howled their anger and their disapproval of Yanichi. This latter, triumphant, appeared to be insensitive to the hostile remonstrations of the public. He went to sit down on the sidelines, beside his compatriot, in the manner of the tailors at work, by crossing his legs beneath him. And while the spectators redoubled their cries, our two Japanese entered into an animated conversation and even laughed together, contemplating the victim who did not give any sign of life. Suddenly, one of them rose, as if driven by a spring, and approached Klemsky. He leaned on the body of the Russian and gave some sort of vibration or massage to the cardiac area, which revived the victim gradually. Then, to the great astonishment of the audience who were now gasping, Klemsky opened his eyes and asked where he was. This seemed magical, and even more than before, Jiu-jitsu appeared to be a most mysterious form of fighting. When someone asked Klemsky for his impression of the event, he said that while losing consciousness he had heard the sound of bells.

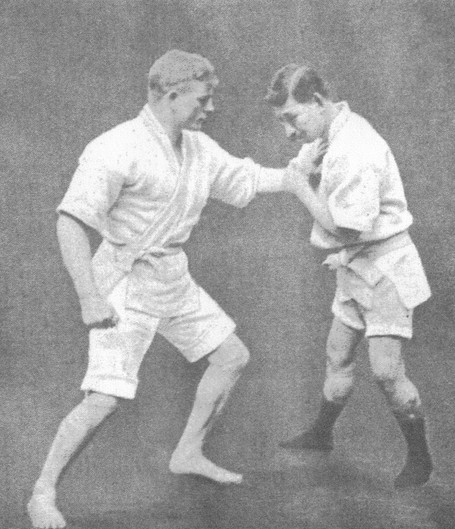

An aura of invincibility soon cloaked the seemingly unbeatable Uyenishi and his fellow countrymen, although, it must be said that most matches were judo contests of which the domestic grappler had little understanding and an even less chance of success. To even out the odds modified catch-as-catch-can rules were sometimes used, albeit with both contestants wearing a jacket. Even under these more "balanced" rules, Uyenishi and Tani almost always proved triumphant.

And this success was not limited only to matches where the rules were tilted heavily in their favor, but also when competing under the English’s own catch-as-catch-can rules. Yukio Tani, after several months of tutelage from the former champion Joe Acton, even managed to capture the "lightweight championship of the world" (or at least a version of it) from the respected wrestler Jem Mellor at the Tivoli in 1904. The Sporting Life, commented after the match that "The little Jap showed what a wonder he was by beating the Englishman at his own game. Two falls to one was the decision, though the fall given against Tani was questioned by many.’ It was thus little surprise that, as victory after victory piled up for the 5 foot, 9 stone fighter, some citizens of London began to view jujutsu as having almost mystical properties.

This view was diminished slightly when Ernest Regnier, still basking in his victory over George Dubous, let his hubris get the better of him and challenged Ivan Paddubny of Russia. Outweighed by 100 pounds and facing one of the greatest Greco-Roman wrestlers of his era, Regnier would be thoroughly trounced, vanishing thereafter from the public eye. But as other arriving Japanese "wrestlers" found the same success as Tani and Raku, jujutsu kept its prestige for some time in London.

Eventually jujutsu would make its way to the shores of the United States, but for whatever reasons, be it the rough "anything goes" style practiced in some regions, the wide-spread familiarity of jacket wrestling amongst a large portion of the population or the fact that the stranglehold and most other "punishing" holds were allowed under the commonly followed American National Police Gazette rules, the States proved to be a much less hospital clime for the Japanese import.

The tone was set immediately by one of the, if not the earliest confrontation between a professional grappler and a jujutsuka in the United States, which took place in Bellingham Washington on September 5th, 1904. In the match, Frank Gotch, perhaps the greatest catch-as-catch-can wrestler in all of history, threw K. Aoyogi three times in all of 32 seconds.

More matches and more defeats for jujutsu soon followed. In Salt Lake City on February 27th, 1905, Eddie Robinson would twice put Kadura Murayam down with ease, in a match where "each man was allowed to use his own style of wrestling."

A few weeks later in, Baltimore, Anthony "Columbus" Wallenofer, the featherweight wrestling "champion", was scheduled to meet Hako, "the jiu-jitsu expert", in a finish match (pin or submission only) where "Everything will go. The Jap will be allowed to use all his foxiest and most mysterious holds, while Columbus will be entitled to do pretty much anything except hit his rival with a club." The bout was to be 3-out-of-5 falls but ended when Hako quit while behind 2 falls to 1, after voicing a complaint about the rules governing the contest. Shortly after that in St. Louis, in what was billed as a "Wrestling Jiu-Jitsu Match" in which no hold was barred, not even the stranglehold, George Baptiste "proved the American system superior to jiu-jitsu", by defeating Arata Suzuki in two straight falls in less than five minutes total time.

The most celebrated match of this period, and often mistakenly listed as the first such encounter, was between George Bothner "the champion lightweight wrestler at catch-as-catch-can style" and Professor Katsuguma Hagashi "one of the foremost experts at the Oriental science in the United States" on April 6 of 1905 at the Central Grand Palace in New York. The much anticipated match received a great deal of press coverage in the lead up to the event, with many expecting "to see the little brown man break Bothner's bones" while others looked forward to Bothner disproving the Japanese’s boasts. Going into the match, Higashi had made something of a name for himself by giving exhibitions where he would throw up to five policemen in a single evening while also proclaiming the superiority of jujutsu over any other form of defense. Particularly grating to wrestling supporters where such comments as:

I have met a number of Western wrestlers, and they are as helpless as babes against the art of jujitsu. And no one versed in the art of jujitsu is mad enough to expect anything else.

The contest between the two was to be a best-of-five combined jujutsu/wrestling match with the agreed upon rules stipulating that "The jiu jitsu man can use in his defense any of the tricks that belong to his art. He also assumes no responsibility for any injury or injuries caused by any act or thing done during the contest, and must be held blameless for any ill-effects or injury that may be received during the match." Each of the men was to wear a "Japanese wrestling costume consisting of short jackets like kimonos with a belt around the waist" and the contest would be to pin-fall or submission, although there seems to be some confusion regarding the length of a pin or how to count "flying falls". After the match there would be a great deal of disagreement as to whether the agreed upon rules had been followed.

http://www.lutte-wrestling.com/841cover.jpg<>

http://cdn1.sbnation.com/imported_assets/853732/841cover.jpg

The New York Times summarized the match:

Bothner got the first fall in the quick time of 14:33 (minutes and seconds) and the second in 1:31:18. The conditions called for the best three falls out of five, but it was long after midnight before the third bout was called. Bothner won this and the match in 12 minutes.

Higashi and his supporters complained vociferously "that he was unfairly treated in respect to a non-observance of the rules that had been agreed" and in this accord they may have been right. Earlier reports indicated that "flying falls", which are common in judo, would be counted but accounts filed from the match seem to indicate that a ten second and then later five second pin was instead required for victory. In any case, many looked at Higashi’s complaints as sour grapes, for with all his earlier boasting of the superiority of jujutsu and of the many deadly tricks at his disposal, "The result was disappointing, that is to those who hoped to see something unusual in the famed jiu-jitsu."

The victory would prove to be the highlight of Bothners career, one he would try to recreate when he faced – and defeated – the judoka Tarro Miyake in his farewell match in 1914. For his part Higashi would soon move to the greener pastures of Europe where he would face – and lose to – YukioTani in a jujutsu match in Paris before making his way to Germany for his encounter with Bob Fitzsimmons.

Jujutsu’s lack of success in the States would begin to change as more talented judokas began to arrive on American soil and try their hand at the professional mat game. One of the more accomplished of the early jujutsukas to do so was 4th-dan Akitaro Ono. Having settled into Asheville, North Carolina shortly after arriving in the US in May of 1905 (to serve as a jujutsu instructor at the Annapolis Naval Academy) he immediately found success in the ring, defeating the 6’5’ 305 lb. "Big Tom" Frisbee in a "jacket match" via stranglehold. With his victory the 5’7" 206 pound Ono became an instant sensation to the people of Asheville, who viewed him and jujutsu as unbeatable. Unfortunately this newfound popularity attracted the likes of Charles Olson to pay a visit and challenge him to a match. Olson, one of the premiere wrestling "ringers" of the era, traveled the country setting up "money matches", were he could clean up on side bets from locals unaware of the reputation he held. In later days the Seattle Daily Times described him thus:

Olsen is a past master of the punishing game. He is a terror to every foe against whom he is in earnest. All the bone-breaking, nerve-wrecking, heart-rending tricks of this most torturing of all sports are at his command. Olsen has long stood in his own light as a wrestler. He has eked out a fortune… by wrestling under aliases in the ‘bushes'.

He was labeled by no less an authority as Frank Gotch as "one of the most dangerous men on the American canvas" . It was a claim that was not without merit: twice during his career he killed his opponent during such "money matches".

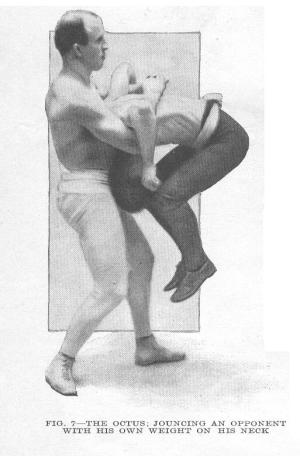

The contest between Olson and Prof. Ono would fittingly be billed as a "blood match", with the rules stating that besides each wrestler being required to wear a judogi, it would be "anything goes". The description would prove accurate as Olson head butted, battered, and strangled Ono for over an hour until one side of his face was beaten into a bloody pulp, and his eyes were so swollen shut that he was forced to concede the match (although the New York Times reports Ono giving in only after being strangled with his own jacket for ten minutes).

Ono’s loss created something of a diplomatic row, with the Japanese consulate protesting the results and Olson’s behavior (let alone the $10,000 he and his associates cleaned up on in side bets), although to no avail. Wrestling had triumphed over jujutsu yet again in America.

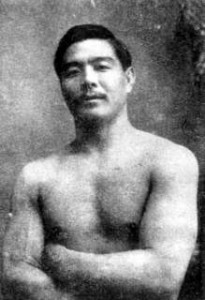

As Ono recovered from the match, he was paid a visit by Esai Maeda, a Japanese countrymen and fellow judoka better known as Matsuyo Maeda. Maeda had come to the US along with Tsunejiro Tomita and Soshiro Satakato on a mission to spread Kodokan Jodo. Maeda had served as Tomita’s assistant, and in this capacity he gave exhibitions as well as took part in several "wrestling matches". Maeda had recently parted with Tomita, and after his visit with Ono, set about to enter the world of professional wrestling.

Maeda would engage in his first confirmed professional wrestling match against Sam Marburger, who was billed as "America’s cleverest wrestler at his weight’ on December 18, 1905 at the Grand Theater in Altanta, Georgia. The results of the contest, which was a best of three, was Marburger taking the single catch-as-catch-can fall while Maeda won both the "Japanese style" (with jackets) falls and the match.

"Score another one for the wily Jap" reported the Atlanta Journal. "When Professor Maeda is under a full head of steam, greased lightning should be classed with the ‘also-rans’." His opponent, Marburger also had nothing but praise for him following the meeting:

"...if you ever hear of that Jap mixing it up with anyone else soon, just let me know. I’d like to put all my money on this unbeatable phenomenon!"

With the victory (and more importantly, the winner’s purse) Maeda took up prizefighting as a career. He, along with the now recovered Ono, journeyed to Europe where he found success not only in "anything goes" matches but also in straight up catch-as-catch-can wrestling. In London in early 1908 he would split two tightly contested and highly praised matches with Henry Irslinger while also capturing second place in the heavyweight division of the prestigious Alhambra open to the world wrestling tournament. Before the end in the year the two would make their way to Latin America, where they would spend the next several years traveling the region and fighting. While in Havana, Cuba, Maeda even tried to arrange a mixed-styles match with the champions of both boxing and wrestling, Jack Johnson and Frank Gotch, but nothing became of it. It was also while in Havana that the pair was joined by two other Japanese jujutsu wrestlers, Maeda’s old companion Satake Shinjiro and another judoka by the name of Tokugoro Ito. Together they became known as the "Four Kings of Cuba". Over the next few years they would crisscross the region - Cuba, Mexico, El Salvador, the Canal Zone, Brazil, Peru - participating in numerous jujutsu, wrestling, and "anything goes" contests.

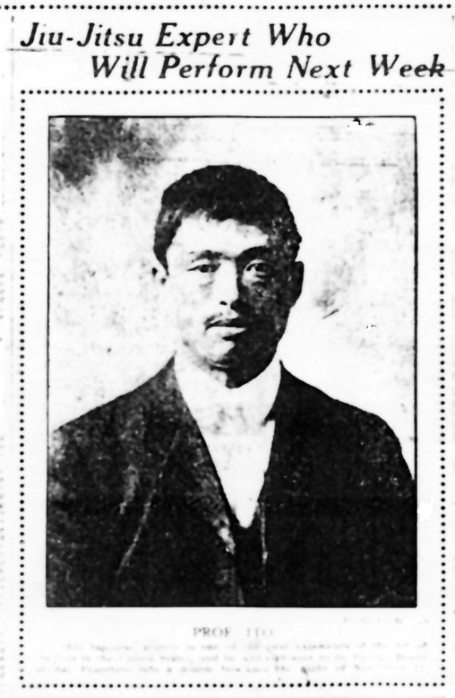

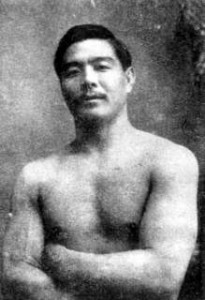

Of the "Four Kings", perhaps none took a more active part in the battles between jujutsu and wrestling - nor found more success against American wrestling - than Tokugoro Ito. Legend has it that a 27-year old Ito left his position as a teacher of judo at the Tokyo Imperial University in 1907 to travel to Seattle, Washington at the behest of the local Japanese population looking for protection from the extortions of Chinese gangsters. Whatever the truth, Ito would take up an instructor’s position at the Seattle Dojo, the oldest judo dojo in America, and, after being promoted to 5th-dan, would soon try his hand at professional fighting.

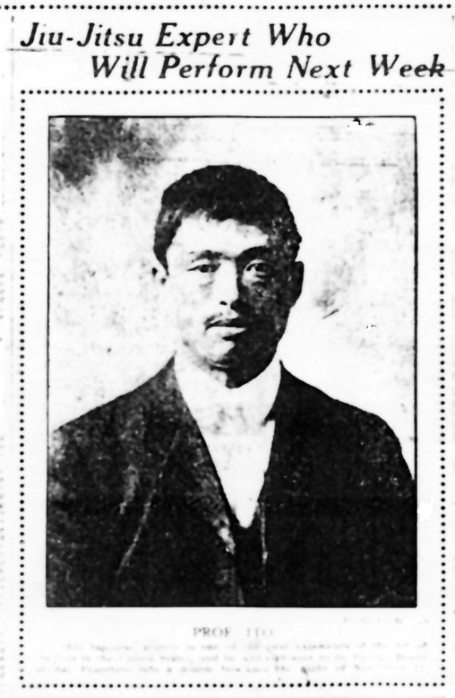

http://cdn0.sbnation.com/imported_assets/853790/ItoPInov61909jpg.jpg

On September 2, 1909 he would engage in his first prizefight against the professional wrestler Eddie Robinson of San Francisco at the Grand Opera House of Seattle for Japan Day. The contest rules called for both men to wear canvas jackets, and with only gouging, biting, kicking, or striking with a closed fist prohibited. Everything else was allowed. The match would end only after one man surrendered unconditionally to the other.

Going into the match, the advantage seemed to lie with the American Eddie Robinson who had had already competed, and found success, against jujutsukas, having beaten Kadura Murayam handedly back in 1905, and felled Shosha Yoyama in Los Angeles in June of 1909. Ito had no such comparable experience against wrestlers. It wouldn’t matter.

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer documented the encounter:

Robinson started out by jabbing Ito three times straight in the face… Before the first bout was two minutes old, blood was flowing from Ito's nose…

Ito locked his legs around the white man and began to 'scissor' him. Next he got a strangle hold, using Robinson's neck cloth as a tourniquet, and slowly forced the American into submission by the process of strangulation. The time was 10 minutes 55 seconds.

The second bout lasted three minutes… Again the Japanese tied on the tourniquet and Robinson's face went red and then black. He was helped to his corner, and in spite of the vicious fight they had gone through, the Japanese was the first to assist Robinson. That was a piece of real sportsmanship.

Ito’s victory led to a quick challenge from George Braun, also of San Francisco, who claimed to have beaten all the best jujutsu men in California (although the his only recorded matches against a jujutsu man - Shosha Yokoyama - indicate that the results were a draw and loss for Braun).

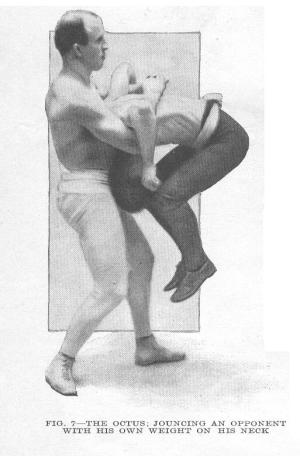

Braun entered the ring for their November 12, 1909, match dressed in a custom-made jacket (for this match the sleeves were to only go to the elbow) which was closed with a belt made from twisted America flags, and boasting that he would eat the Japanese alive. Ito was outraged by Braun’s attire, and the fight was delayed while he was made to replace the offending garment. When the match finally did get underway the Seattle Times was there to record the action:

When the men shaped up for the first bout Ito stood erect in an easy attitude watching the Frisco champion make a lot of silly motions with his hands and grimaces with his face. Finally Braun lunged in and got hold of Ito's jacket. The Japanese broke the hold easily and grabbing Braun by the collar he kicked his feet from under him and slammed him to the mat heavily. In a twinkling Ito got a strangle hold and flopping over on his back he wrapped his legs around Braun, rolled off the canvas with him and calmly waited for Braun's wind to be shut off…

It had taken Ito all of two minutes and twenty seconds to win the first fall. The second was even less competitive as Ito choked out Braun in just forty-three seconds.

Ito’s next match was March 16, 1910, against Julius Johnson, the 1908 Northwest AAU middleweight wrestling champion and the wrestling coach for the Norwegian Turners. While the match would again take place in jackets, Johnson’s weight advantage (160 pounds to 143 pounds) was though to even out the odds. It didn’t as Ito won again in two straight falls using what was described as a "erijime" and a "hadakaji".

The Post-Intelligencer also offered the following opinion about these sort of matches:

There is more excitement packed into one minute of jiu-jitsu than in ten rounds of boxing or ten days of wrestling. The hand-to-hand, body-to-body style of combat, the rough-and-tumble rules, as well as no small measure of racial feeling, stirs the blood of the spectators. White and brown men were carried off their feet last night by the furious work of the two combatants, and the opera house was a pandemonium while the wrestlers were struggling on the canvas mat.

Next up for Ito was Joe Acton on May 18, 1911, although there is some confusion as to which Joe Acton it was. According to Mark Hewitt, it was "Young" Joe Acton who was actually Joe’s younger brother Matt. Other evidence point to it actually being the "Little Demon" who had taken on the boxers Bob Fitzsimmons and Professor Miller decades earlier and who had wrestled Yukio Tani back in 1904. If it was the elder, more famous of the two, he would have been 59 years old at this time.

But whatever Joe Acton he faced, the results were more of the same. According to Henry Furukawa, writing in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer on May 21, 1911:

Ito threw his opponent on 'Hijaguma,' and before he could get on foot grabbed Acton on his jacket collar and choked him breathless in three minutes, ending the first bout. Acton was actually dazed and seemed unconscious for a few moments.

The second bout was over in two minutes, Ito getting the dreadful arm hold in a short time and Acton gave in. In all Prof. Ito's jiu-jitsu matches in Seattle he won them in such deciding manner that his opponents looked like nothing but 'dubs.'

Ito’s next contest would be his first outside of Seattle. On the evening of June 9, 1911 he met Farmer Watson in Portland in a two-out-of-three falls match. The first fall ended after 5 minutes, 33 seconds, with Ito getting an "armbar stranglehold", which left Watson unconscious for almost a minute. The second took three minutes, when Watson couldn’t escape another stranglehold.

After this match, Ito would leave his position at the dojo and Seattle and set out on an extensive tour of Latin America, where he teamed with the other "Four Kings" much of the time. For the next four years he would travel all throughout Latin America, engaging in numerous matches, including, according to Ito, a match against the "champion of Panama" and another against the two best heavyweight wrestlers of Peru – beating them simultaneously in under a minute. After several years of wandering he decided to return to the United States, parting ways with the other "Kings" while they were making a tour of Brazil.

Upon his return to the States Ito set up residency in San Francisco where he quickly went about looking for prizefights. His first match would be on February 5th of 1916, in San Francisco against the 5’9’ 180 pound Ad Santel, a highly skilled catch-as-catch-can wrestler and claimant to the World’s Light Heavyweight Championship. Santel was not a complete novice with regards to jujutsu, having faced and defeated the self-professed 8th-dan Senryuken Noguchi in November the previous year. The experience paid off, for shortly after the match started, Santel was able to grasp Ito, pick him up, and slam him head first into the ground. The impact gave Ito a concussion and he was unable to continue, resulting in a victory for Santel – and Ito’s first loss.

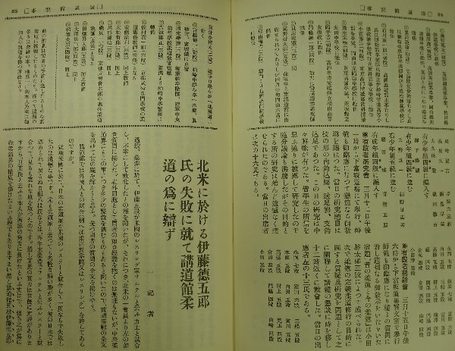

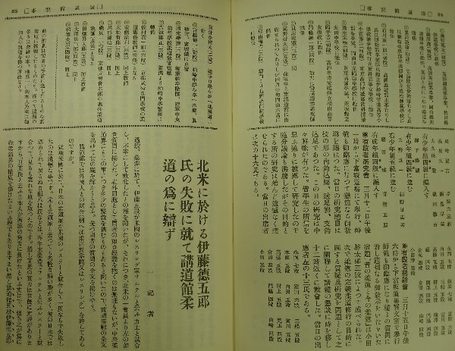

The defeat caught many in Japanese community off guard and the Kodokan felt the need to comment on the matter:

Regarding this match, the Kodokan noted that Mr. Ito had been away from Japan for number of years, and the lack of opportunity to train with stronger opponents may have contributed to his lack of judo ability. In addition, his fifth degree judo rank did not mean that his knowledge represented the ultimate in judo technique. In fact, fifth degree was the mid-point in ranking between first to tenth degrees. Therefore, the Kodokan concluded that Mr. Ito's loss did not reflect negatively on the efficacy of judo techniques, but instead on the poor showing of Mr. Ito.

Looking to avenge this blemish on his record Ito immediately set up a rematch for June 10, 1916. The outcome of this contest was recounted by Howard Angus in the Los Angeles Times:

Ito threw Santell around the ring like a bag of sawdust… When Ad gasped for air, the Japanese pounced upon him like a leopard and applied the strangle hold. Santell gave a couple of gurgles, turned black in the face and thumped the floor, signifying he had enough.

His sole loss avenged, Ito continued to wrestle for the next few years, defeating the likes of the strongman Wilhelm Berne, the Greek wrestler Gus Kerveras, and the talented catch-as-catch-can proponent Ted Thye, all in straight falls, before finally retiring from the fight game and returning to Japan in late 1921 or early 1922.

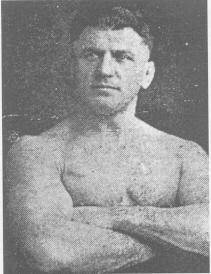

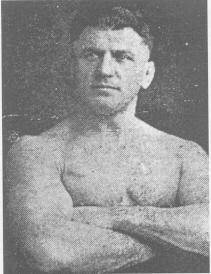

http:// http://cdn0.sbnation.com/imported_assets/853802/post-13-1097020228.jpg

For his part, Ad Santel had only begun his personal odyssey against jujutsu. On October 20th, of 1917 he traveled to Seattle and met Taro Miyako, who he defeated using the slam once again, causing Miyake to experience "dizzy spells for half an hour after the fall." Two weeks later he would face and defeat another Seattle Dojo judoka instructor in Kodokan 4th-dan Daisuke Sakai.

With this string of successes, Santel put together a troupe of wrestlers, including Henry Weber and Matty Matsuda, for a tour of Japan in early 1921, during which he issued a challenge to the Kodokan itself. For its part, the Kodokan, which frowned on professional sports, ordered its judoka not to partake in any such matches, but several of its more distinguished members chose to ignore the edict. For two straight days in March a wrestling versus judo card was held at the Yakushuni Shrine Sumo Hall, On the first night Santel faced and either drew or knocked out 5th-dan Reijiro Nagata, while the following evening, his match with 4th-dan Hikoo Shoji was ruled a draw after they battled for three twenty minute rounds. A few night later, Santel was in the city of Nagoya, to face, and defeat, Hitoshi Shimizu, in his last such match in Japan.

Upon his return to the United States Santel would magnify his feats in Japan, claiming that he had faced and beaten the top judokas of the Kodakan and had captured the World’s Jiu jitsu (or Judo) Championship. He even went so far as to defend this imaginary title against other professional wrestlers in "Jiu Jitsu matches" during the 20s and 30s.

Santel and Ito’s encounters were very representative of the "anything goes" matches that were taking place in the United States in the second decade of the Twentieth Century. They had evolved out of the jujutsuka versus wrestler contests, developing their own codified set of rules: "no holds were barred" allowing contestant to use the full gamut of jujutsu, Greco-Roman, and catch-as-catch-can holds, even those that induced pain and injury; they could be fought either with or without jackets; they were decided by submission or incapacitation, although victory by pin-fall was sometimes allowed as well; in some cases striking with an open hand and kicking were permitted.

In Australia these matches were known as "all-in", having come directly out of the increasingly popular mixed competition fights, and allowed for contestant to use all the tactics and techniques of wrestling, boxing, and jujutsu. It would seem a new combat sport was taking form, although in truth it was not all that new.

When Clarence Weber made his "challenge to fight Jack Johnson ‘all-in’ and thus prove the supremacy of the white race", it was not lost on observers that they would actually be electing to "fight under the Greek Pancratium rules" (although pancratium was actually the Roman name for what the Greeks called pankration) . A mixture of wrestling and boxing "in it nothing is barred except biting, eye-gouging, and attacks on certain vital spots. Everything else is admissible. The kidney punch, the strangle hold, the double Nelson, and other methods of offence ruled out under different codes, may well be brought into action." After 1500 years of dormancy the ancient sport and martial art of "all powers" was gaining a new life on the professional wrestling circuit.

There had, in fact, been earlier attempts to actually resurrect the pancratium. In 1883, the Olympic Athletic Club in San Francisco had even hosted actual pancratium matches (along with the Roman cestus, a brutal form of gladiatorial boxing, using wool instead of iron gloves), pitting bare-knuckle pugilists and catch-as-catch-can wrestlers in grappling matches where open hand strikes were allowed, as part of their "Roman Revival" at the Mechanic’s Pavillion. While it was enormously successful with the attending audiences it was also a massive financial failure, and future events were abandoned.

http://cdn1.sbnation.com/imported_assets/853799/inkersley_3.jpg

In 1898, R. Logan-Browne in "Health and Strength Magazine" wrote about the efforts of a group of Englishmen to develop a sport they had named "Neo-Pancratium", declaring "that the ancient Pancratium, suitably adapted, might afford us an excellent method of physical culture and athletic contest, with the additional benefit of being a secure and versatile method of self-defence against roughs and thugs."

He went on to explain that "In re-constructing Pancratium for the modern age, our raison d’etre has been that whilst blows are legitimately outlawed in wrestling, they are the boxer’s stock in trade, and whilst gripping and throwing are banned in the ring, they are practiced safely by wrestlers everywhere. By combining these two sports we may approximate the Pancratiast’s art in all but its most savage aspects, thereby enjoying its benefits without suffering its excesses."

While in the upright position Neo-Pancratium would use boxing as its model but "Where Neo-Pancratium differs significantly from modern boxing is that, when devotees of the purely pugilistic art close together, they are immediately parted by the diligent referee. The Neo-Pancratiast, by comparison, simply segues from boxing into wrestling and continues his contest." On the ground it was decided that Lancashire wrestling would be the most suitable because the "Catch-hold school offers the option of forcing one’s adversary to surrender through painful holds applied to the joints of the limbs, exactly as was the custom in ancient Greece."

One problem cited by the author in developing this new sport was that "the modern glove, so crucial in cushioning the force of a blow, becomes an absolute handicap when wrestling… The solution has been to devise a novel form of glove, rather more open in the palm and with room for the fingers to grip securely, yet well-padded across the knuckles. This innovation allows Neo-Pancratiasts to successfully move between boxing and wrestling as required by the exigencies of any given contest. The Committee is presently undertaking discussions with a leading purveyor of sporting goods and hopes to be able to offer these new gloves to the public in the not-distant future." (A decade later it was still a problem, as Mr. Grainger of the Japanese School of London and Jean Joseph-Renaude, the author of "La Défense Dans La Rue", where both asking inventors to assist in designing a glove that could be used in mixed boxing and jujutsu matches.)

While nothing became of Neo-Pancratium, "all-in" seemed well on its way towards becoming an established style of wrestling. In fact, if one looked at the rules that governed professional wrestling in the 1930s - rules that are usually credited to Toot’s Mondt and his introduction of "Slam Bang Western Style Wrestling" into the business - it becomes apparent that they had been derived directly from the "all-in" matches of the previous era. The only difference is that now they were no longer contested for real, as "worked" wrestling had become the norm.

The end of this "Golden Age of Ultimate Fighting" began with the first shots fired in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914. For the next four years Europe would be engulfed by "The War"; amongst the casualties would be the mixed fights that had been popular only a few years previous, swept away suddenly by the forces of history.

The War would also spell the end of the mixed competitions in the United States. For a multitude of reasons, professional wrestling, the driving force behind mixed competitions, would move from an often-worked-but-still-legitimate sport to pure vaudeville. A proposed million dollar contest between the champions of wrestling and boxing, Ed "The Strangler" Lewis and Jack Dempsey, could have perhaps rescued it from this fate, but in the end the match failed to materialize and legitimate contests were now a thing of the past.

Only in Asia did mixed fighting continue, at least for a few more years. In July of 1925 Ad Santel visited the islands of Hawaii to meet and draw with another jujutsuka in Tsutao "Rubberman" Higami. In December of that year Seishiro Okazaki met a boxer calling himself "Kid" John Morris who claimed to be the younger brother of Okazaki’s previous victim and who had come to avenge his sibiing. The match was to be a three round affair, and when it went the distance Okazaki left the arena, unwilling to continue. To stave off a riot, Higami was drafted to continue against Morris, winning after two round by arm bar. Afterwards the The Hilo-Herald Tribune called for an end to mixed matches:

this paper is of the opinion that a mixed match of this kind between a Japanese jiu- jitsu expert and a white boxer is not a good thing for this community. It serves no good purpose and merely arouses useless race prejudice.

Jiu-jitsu is something that the Japanese think undefeatable while the Anglo-Saxon thinks the same of boxing, and both methods are practically rooted in each classes’ national pride. When either meets defeat at the other’s hands, age-pride of caste and country is aroused and good sportsmanship is bound to suffer....

While such matches where no more in Hawaii they continued a little longer in Japan. But eventually due to the violence they incited along racial lines (according to the Japan Times, on July 24th, 1925, in Hokkaido, two judokas were stabbed to death after embarrassing some foreign boxers) or the increase in popularity of "kunto" - actual boxing - amongst the greater population, these contests stopped being held, marking the end of a "Golden Age."

Fortunately for us, as the misquoted George Santanyana aphorism tells us, "Those who cannot remember the past are doomed to repeat it."

EPILOGUE

The lamps are going out all over Europe. We shall not see them lit again in our time.

- Sir Edward Grey

For the field of martial arts the Belle Époque was a remarkable time, one that saw unrivaled achievements and previously unimaginable accomplishments. Wrestling would evolve from a regional activity were participants competed in local folkstyles to an international spectator sport where all the elements of the world's grappling systems where melted down into what became known as American style catch-as-catch-can. Jujutsu would be rescued from extinction and then go on to rapidly spread across the globe thanks to Kano Jigoro's revolutionary Kodakan judo. In London and Paris Eastern and Western disciplines would be merged giving birth to the new hybrid fighting styles of Bartitsu and defense dans la rue. And fighters representing the various disciplines of the world would be pitted against each other in mixed competitions and no-holds-barred "all-in" matches, testing the skill of the combatants and the merits of their "art". It was truly a Golden Age for martial arts, one that burned very bright.

It would not last.

Europe was the first to go dark. From June 28, 1914 until November 11, 1918, the continent was transformed into a vast charnel house by the "War to End All Wars". A whole generation of young men were killed, maimed, or traumatized by the hell that was the Great War. In France, a nation of 40 million, 1.4 million soldiers perished and three times that number were wounded in the conflict. That is, half of the previously able bodied male population was now either dead or maimed, while many, many more suffered from the debilitating effects of ‘shellshock". The United Kingdom did not fair much better, with nearly 900,000 left dead on the battlefields. Germany saw over 2 million of their young men exterminated. Millions more from Russia, the Austrian-Hungary Empire, Turkey, Romania, and the other nations of Europe, not to mention the dominions and colonies, had their names added to the grave markers. Even more were lost when an pandemic of Spanish Flu spread across the globe, assisted by the conditions created by the war, killing between 50 million to 100 million more, with the young tragically being the most at risk of dying.

http://cdn3.sbnation.com/imported_assets/863945/2m5l0mr_jp.jpg

Martial arts would not be spared from this conflict, for in the end, the generation of Europeans that had taken such a great interest in the "antagonistics", that made wrestling a widely practiced and popular sport, that had taken up the study of Japanses jujutsu, who had developed various "arts of self defense" to defend against the night attacks of les Apaches and Hooligans, were almost completely wiped out. And even amongst those that survived the horrors of the trenches "unscathed" we can not underestimate the psychological effect that such an experience had on them and society. How good was wrestling, jujutsu, boxing, or savate when one was faced with machine guns, poison gas, artillery, and aeroplanes?

Almost overnigt the Golden Age turned dark in Europe, and like ripples across a pond, the rest of the world couldn't escape the repercussions.

The United States was a late entrant into the War, and for that reason suffered much less than those in Europe, but it too suffered and amongst its many casualties was professional wrestling. Always prone to hippodroming and match-fixing, it was still nevertheless more-or-less as legitimate of sport as, say, boxing or bicycle racing. But during the war years it underwent a complete transformation from being merely a "tainted" sport to one of choreographed theatre. One of the reasons, as theorised by Mathew Lindaman in his essay "Wrestling's Hold on the Western World Before the Great War", is that the change was brought upon by modernity. Thanks to such technological advances as the automobile, aeroplane, cinema and the wireless, the world was a much faster place, and the people who occupied it desired their entertainment to match that pace. So gone went the grueling 5 hour bouts to be replaced by "worked" matches, which would quarantee the speed and action fans were now demanding.

The other reason for this move towards completely "worked" wrestling was that the war provided the American stars and promoters the opportunity, which they took, to cement their continued control of industry and their place as headliners. The chance to do so had arisen thanks to the loss of the European wrestlers and the mobilization of some 4 million American males, meaning that during the conflict, a much fewer number of talented but unestablished wrestlers could challenge the postion of those already working. And by careful matchmaking with arranged outcomes these "stars' were able to remain at the top - and would remain there as long as the wrestling stayed "worked". Thus professional wrestling (long the driving force behind combatives in North America) of any legitimate nature died and with it the Golden Age in North America.

Japan and the rest of Asia held out the longest, being left relatively unscathed by the War, but even there they couldn't escape its aftereffects. Where before the world had been getting smaller, with the open exchange of ideas resulting not only in the spreading of jujutsu to the West, but the introduction of professional wrestling, boxing, and mixed competition "merikan" fighting to the nations of the Pacific, suddenly in the wake the war, a vast divides and gulf existed between the nations were none existed before. Trade and travel (except for the vast amount of troops on the move) had plummetted during the conflct, with the world economy only reaching its pre war levels in 1925 (and then for only four year before a Great Depression descended on the world). Nationalism and xenophobe were exerberated by the fighting: suddenly foreign ideas and imports lost the appeal they exuded beforehand. And these barriers only got worse as the world begin choosing up sides between communism, democracy, imperialism, and fascism in the dark day afterwards (only ending when another greater slaughter got under way). Eventually the great exchange of fighting disciplines and techniques between East and West died out, and the flame, that had burned so bright only a generation before, faded and died. And thus the Golden Age passed from history, its achievements disregarded, its accomplishments apparently doomed to be forgotten by the world at large.

With one exception.

In November of 1914, less than four months after the great powers had gone to war, Matsuyo Maeda arrived in Brazil. For the previous decade the judokan had been traveling the world engaging in not only jujutsu matches, but also catch-as-catch-can and "anything goes" competitions. His experiences led him to add Western wrestling techniques and methods for confronting boxers to his repertoire of skills. For the next year he would travel through the South American republic along with a troupe of fellow Japanese jujutsu practitioners giving exhibits and offering the traditional at show challenge to "face all comers". Eventually he and his compatriots would find their way to the Northern City of Belém where, on Christmas Eve of 1915, he engaged in a mixed competition bout with the boxer Adolpho Corbiniano of Barbados, defeating him in seconds (Carbiniano would become a pupil of Maeda's after the loss). A week later, on January 3, 1916 Maeda defeated the Greco-Roman wrestler Nagib Assef by armlock.

The fire, now dying in Europe, had been passed to Brazil.

Maeda resided in Belém for several years, where he taught his own brand of judo and (after supposedly facing and defeating the knife-armed capoeirista Pé de Bola in 1918 in a truly "anything goes" match) retired from prizefighting. Amongst his students during his time in Belém was a young man named Carlos Gracie who would himself go on to teach what he learned on the mats with Maeda to his own brothers..

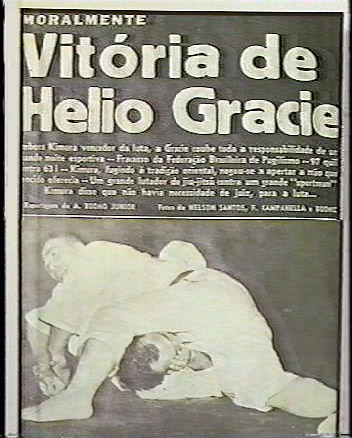

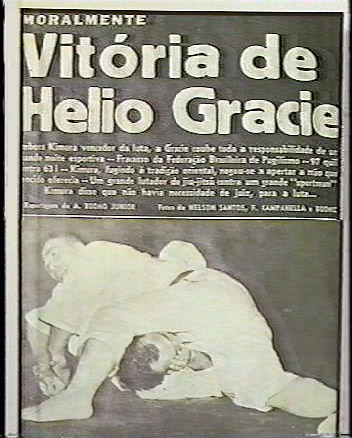

While in the rest of the world mixed competitions had vanished, in Brazil the "anything goes" matches introduced by Maeda and his ilk not only survived but flourished with boxers, jujutsukas, capoeiristas, and both luta livre and Greco-Roman wrestlers taking part. Amongst these fighters numbers were Geo Omori, Manuel Rufino, Dudu,and the Gracie brothers: Carlos, George, Oswaldo, and the youngest, Hélio. Hélio would continue taking part in such matches, which became known as "vale tudo" or "no rules" in Brazil, for decades to come, with a career highlighted by matches against the North American professional wrestlers Wladek Zbyszko and Taro Miyake, his former student Valdemar Santana, and perhaps most famously, the judoka Masahiko Kimura. Hélio would pass on his system of fighting and an appreciation for "no holds barred" combat to his children.

Eventually Hélio's eldest son, Rorion, would move to the United States in hopes of spreading the family's system of self defense. He would also bring with him the concept of vale tudo, which served as an inspiration for an event held in 1993 known as the "The Ultimate Fighting Championship". The flame, handed down from Maeda to Carlos to Hélio to Rorion had now been spread to the world at large, and a fire that had been extinguished 70 years ago was finally re-lit.

A new age of mixed martial arts had began.

Sources are either listed or linked within the article. A number of sites and researchers proved to be invaluable for the material, including images, seen here. And so I would like to thank: Mark Hewitt (and his Catch Wrestling and Catch Wrestlng: Round Two), Jonathan Snowden (and his Total MMA), Joseph Svinth, Graham Noble, Tony Wolfe (and his Bartitsu Compendiums), The Bartitsu Society, The Bartitsu Forum, and the Electronic Journal of Martial Arts. And a special thanks to the Continentalop and Cowboy for their much appreciated input, advice, and suggestions.

That concludes The Forgotten Age of Mixed Martial Arts.

[Note: many of the passages from contemporary sources contain derogatory and offensive terms in reference to various ethnic groups. While I in no way condone the viewpoints expressed with their use, I also do not condone pretending such sentiments did not exist. For that reason they have been left in and hopefully do not detract from your reading experience.]

This is part four in a four part series shining a gas light on the forgotten golden age of mixed martial arts that existed during the Belle Époque. For the previous installments in the series, check out Part 1: The Golden Age of Wrestling and the Lost Art of American Catch-as-Catch-can, Part 2: The Rise of Judo and the Dawn of a New Age, and Part 3: Sherlock Holmes, Les Apaches, and the Gentlemanly Art of Self Defence. And for the history of the origins and early development of MMA, read James Figg: The Lost Origins of the Sport of Mixed Martial Arts.

The way the Ultimate Fighting Championship was created was a bunch of television guys got together and said, "Let's answer the age-old question, which fighting style is the best?" Would a boxer beat a wrestler? Would a kung fu guy beat a karate guy?

- Dana White

The fact is that when started this, it didn’t exist. We started it… they didn’t know what it was…

- Bob Meyrowitz, TOTAL MMA by Jonathan Snowden

Autumn of 1993 proved to be pivotal season in the history of combative sports. In September of that year Masakatsu Funaki’s Pancrase held their inaugural event, one where, for the first time in memory, professional wrestling matches were contested for real. It was only fitting that a promotion named after the ancient Greek sport of pankration, a sport that combined boxing and wrestling in an "anything goes" contest, would now be hosting matches where slams, kicks, punches, knees, elbows (but no strikes to the head except for those with an open hand), and all the "sleeper holds", leg locks, and other submission hooks of "worked" pro wrestling would finally be used for real.

A few weeks later, on November 12, an even more significant event took place: the initial Ultimate Fighting Championship. Advertised as a "no holds barred" contest between a "sumo wrestler, savate champion, kick boxer, karate specialist, jujitsu whiz, cruiserweight prizefighter, "shootfighter" and tae kwon do expert" to find the ‘Ultimate Fighter". "People were intrigued by the concept of style versus style." Dave Meltzer explained in Total MMA, "People have debated that forever. What if a wrestler fought a boxer or a jiu-jitsu guy?" The event would prove a success, capturing the public’s imagination and giving birth to what would be known as mixed martial arts, a sport the likes of which the world hadn’t seen since pankration went extinct 1500 years ago.

Of course, anything go matches had not died out with the Greeks and Romans, and mixed fights between boxers, wrestlers, savateurs, judokas and other disciplines had already taken place, having answered all our questions during the era known as the Belle Époque.

The "age-old question" of who would win between a boxer and a wrestler is one that was actually rarely asked until the 20th century. Before that, in the time of London Prize Fighting, the two disciplines were so intertwined that such a debate would be viewed as pointless: a great number of boxers were wrestlers and a great number of wrestlers were boxers. Being skilled in wrestling was in fact viewed as essential to any boxer, with many victories gained due more to grappling and throwing your opponent to the ground than to the power or precision of one’s strikes. For evidence, one needs only look at the 1825 training manual "The Art and Practice of Boxing" by A Celebrated Pugilist (Anonymous) where they will find that of the eight illustrations contained within, nearly half are dedicated to such "boxing" techniques as the "cross bullocks", "throwing", and "locks".

Mixed competitions between wrestlers and boxers (or, more precisely, wrestlers who boxed and boxers who wrestled) did take place, but were viewed very differently than later discipline versus discipline match ups. They instead often resembled the mixed wrestling matches of the time, were wrestlers would compete in two or more styles (catch-as-catch can, collar-and-elbow, Greco-Roman, Cornish, Cumberland, Westmorland and even sumo), alternating between them after every "fall" in a best of three or best of five contest. One such mixed boxing and wrestling match was arranged between William Muldoon and the Australian Professor William Miller in the city of Baltimore on the 25th of June, 1888. Unfortunately, only the first match of boxing was completed (with Professor Miller gaining the decision in 12-rounds over the "Solid Man" Muldoon with both men wearing 4 ounce gloves) before the police stopped the illegal prizefight.

A year later in Gloucester, Maine, Muldoon faced off against his pupil, the "champion of all champions", bare-knuckle boxer John Sullivan, in the best remembered boxer versus wrester contest of this period. Muldoon had been training the "Boston Strong Boy" for his upcoming bout with Jake Kilrain, and his methods, while affective, were so harsh and sadistic that by this time John had come to despise Muldoon. The match itself was 2-out-of-3 falls and Sullivan made a good showing, gaining the first fall, but eventually, as the New York Sun reported, "Wrestling Gladiator William Muldoon tossed Pugilist Gladiator John L. Sullivan." After winning the second round, Muldoon would go on to take the third and deciding fall when "he just picked Sully up and slammed him to the carpet…the fall seemed heavy enough to shake the earth." Following his defeat Sullivan raised his fist and threatened his tormentor Muldoon with a sledgehammer blow but by this time the crowd of 2,000 spectators had rushed the ring, preventing any post-match altercations.

Another famed wrestler of the period who engaged boxers was the catch-as-catch master, Joe Acton, who not only faced the previously mentioned Professor William Miller in Philadelphia in 1888 but the future World Heavyweight champion Robert "the Freckled Wonder" Fitszimmons in San Francisco in 1891 as well. The Angeles Times reported the latter outcome as: "The Pugilist Secures One Fall, but the "Little Demon" Proves Too Much for Him in the Two Other Bouts". Afterwards, Bob Fitzsimmons would himself go on to meet William Muldoon’s chosen heir to the Greco-Roman Championship, Ernest Roeber, in a series of matches that included wrestling, boxing, an alternating mixed competition, and even reportedly a true boxer versus wrestling match in which "Fitz took a punch or two. Then Roeber grabbed him, tied him into knots, and the show was over."